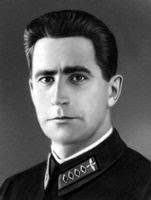

After graduation from the Red Army Military Academy (1921–1924) Alksnis was appointed the head of logistics service of Red Air Forces; in 1926 deputy commander of Red Air Forces. In 1929 he received wings of a fighter pilot at the Kacha pilot's school in Crimea and was later known to fly nearly every day. Defector Alexander Barmine described Alksnis as "a strict disciplinarian with high standards of efficiency. He would himself personally inspect flying officers... not that he was fussy or took the slightest interest in smartness for its own sake, but, as he explained to me, flying demands constant attention to detail... Headstrong he may have been, but he was a man of method and brought a wholly new spirit into Soviet aviation. It is chiefly owing to him that the Air Force is the powerful weapon it is today." According to Barmine, Alksnis was instrumental in making parachute jumping a sport for the masses. He was influenced by one of his subordinates who has seen parachutists entertaining public in the United States, at the time when Soviet pilots regarded parachutes "almost a clinical instrument".

In the same year he was involved in establishing one of the first sharashkas – an aircraft design bureau staffed by prisoners of Butyrki prison, including Nikolai Polikarpov and Dmitry Grigorovich. In 1930–1931 the sharashka, now based on Khodynka Field, produced the prototype for the successful Polikarpov I-5. In June 1931 Alksnis was promoted to the Commander of Red Air Forces, while Polikarpov and some of his staff were released on amnesty terms. In 1935, Red Air Forces under Alksnis possessed world's largest bomber force; aircraft production reached 8,000 in 1936

The first Five-Year Plans triggered a massive buildup of

Soviet aviation, including many airplanes of indigenous design. Among them were

maneuverable fighter biplanes, such as the Polikarpov I-15 and I-15 bis; the

first cantilever monoplane with retractable landing gear to enter squadron

service, the Polikarpov I-16; and a variety of bombers, including the Tupolev

TB-7, SB-2/SB-3, and DB-3.Yet the Soviets failed to develop a reliable

long-range bomber force. The established Soviet concept of air warfare

envisioned the use of airpower predominantly in close support missions and

under operational control of the ground forces command.

The Red Army Air Force under the command of Yakov Alksnis

during 1931–1937 developed into a semi-independent military service with a

combat potential, good training, and a logistics infrastructure spreading from

European Russia into Central Asia and the Far East. Still, the Red Army Air

Force exhibited marked deficiencies in several local conflicts (e.g., against

the Chinese in 1929 and in the Spanish civil war, 1936–1939). In contrast,

during the 1937–1939 air conflicts with Japan (China, Lake Khasan, Khalkin Gol)

the Soviets effectively challenged the Japanese air domination and provided

decisive close air support in the campaigns on Soviet and Mongolian borders.

During the Winter War with Finland (1939–1940), however, the Red Air Force

suffered heavy losses due to inflexibility of organization, its command-

and-control structure, poor training of personnel, and deficiency of equipment.

The failures in Soviet airpower were reinforced by the

terror of Stalinist purges. About 75 percent of the senior officers were

imprisoned or executed, and some 40 percent of the officer corps was purged.

The result was the critical decline of experience, initiative, and

responsibility within the command of the air force and its combat personnel.

The main reason for the large aircraft losses in the initial

period of war with Germany was not the lack of modern tactics, but the lack of

experienced pilots and ground support crews, the destruction of many aircraft

on the runways due to command failure to disperse them, and the rapid advance

of the Wehrmacht ground troops, forcing the Soviet pilots on the defensive

during Operation Barbarossa, while being confronted with more modern German

aircraft. In the first few days of Operation Barbarossa the Luftwaffe destroyed

some 2000 Soviet aircraft, most of them on the ground, at a loss of only 35

aircraft (of which 15 were non-combat-related). Many of these were obsolete

types, such as the Polikarpov I-16, and they would be replaced by much more

advanced aircraft as a result of both Lend-Lease and the miraculous transfer of

the Soviet aviation industry eastward from European Russia to the Ural

Mountains. The sporadic Soviet retaliatory strikes were poorly coordinated and

led to devastating losses in aircraft and combat personnel.

World War II caught Soviet aviation unawares—more than 1,200

aircraft were lost on the first day of the Nazis’ June 1941 invasion. For the

next 6–8 months, aircraft and other factories were shifted eastward to the

Urals and Siberia, a huge undertaking largely completed by early 1942.

Relocation made transport of finished aircraft to the fronts more difficult,

but by late 1942 and in 1943 Soviet aircraft began to appear in huge numbers. Germany’s

output was exceeded in 1943. Fighters such as the Yak-3 and Yak-9 (more than

16,000 of the latter), Lavochkin La-5 (10,000), and La-7 (nearly 6,000) began

to take a toll on German air strength. The Ilyushin Il-2 attack plane was the

most-produced plane in the war (1,000 made every month after 1942 for total of

over 36,000), and the later Il-10 reached production numbers of 5,000.

Luftwaffe reconnaissance units worked frantically to plot

troop concentration, supply dumps, and airfields, and mark them for destruction.

The Luftwaffe's task was to neutralize the Soviet Air Force. This was not

achieved in the first days of operations, despite the Soviets having

concentrated aircraft in huge groups on the permanent airfields rather than

dispersing them on field landing strips, making them ideal targets. The

Luftwaffe claimed to have destroyed 1,489 aircraft on the first day of

operations. Hermann Göring — Chief of the Luftwaffe — distrusted the reports

and ordered the figure checked. Picking through the wreckages of Soviet

airfields, the Luftwaffe's figures proved conservative, as over 2,000 destroyed

Soviet aircraft were found. The Luftwaffe lost 35 aircraft on the first day of

combat. The Germans claimed to have destroyed only 3,100 Soviet aircraft in the

first three days. In fact Soviet losses were far higher: some 3,922 Soviet

machines had been lost (according to Russian Historian Viktor Kulikov).The

Luftwaffe had achieved air superiority over all three sectors of the front, and

would maintain it until the close of the year. The Luftwaffe could now devote

large numbers of its Geschwader to support the ground forces.